At the end of July, CMS announced that enrollee premiums for Medicare’s outpatient prescription drug benefit, known as Part D, will remain stable for 2016 at an average of $32.50 per month. That estimate was developed by CMS’s Office of the Actuary and reflects bids that drug and health plan sponsors submitted for providing basic drug coverage to enrollees in 2016, as well as anticipated effects of some beneficiaries switching to plans with lower premiums. It marks continued good news for Part D enrollees, whose average premiums have remained at about $30 to $32 per month for the past 7 years.

However, other trends are more worrisome for the taxpayers supporting the Part D program. Just one week earlier than the CMS announcement, Medicare trustees reported that aggregate Part D spending grew by 12.1 percent in 2014, largely due to high-cost specialty drugs and especially new treatments for hepatitis C. Medicare trustees see additional spending for specialty drugs on the horizon, keeping growth in program spending high. Between 2014 and 2024, the trustees project that aggregate Part D spending will grow by an annual average of 9.7 percent, compared with annual averages of 5.9 percent for Part A and 7.6 percent for Part B spending.

If Part D plans are experiencing rapid growth in spending for specialty drugs, why aren’t we also seeing Part D premiums rise sharply? The answer can be found in one of Part D’s risk-sharing provisions called individual reinsurance. (See this blog post for a primer about all the mechanisms Medicare uses to share risk with private Part D plans.)

Through individual reinsurance, Medicare pays plans 80 percent of benefit costs above Part D’s out-of-pocket threshold (about $7,500 in 2016). When plan sponsors bid to provide Part D benefits, they submit estimates of how much they expect their enrollees will spend on drug benefits in the coming year as well as how much reinsurance they expect Medicare will pay them. CMS applies a formula set in law that determines Medicare’s monthly fixed-dollar payments to plans (called the direct subsidy) as well as the plan’s monthly enrollee premium. The combination of Medicare’s reinsurance payments and direct subsidy payments lower Part D premiums by about 75 percent compared to what enrollees would otherwise pay. After the end of the benefit year, CMS and plan sponsors review claims data to “true up” Medicare’s reinsurance payments compared to estimates that sponsors submitted in plan bids.

In all but two years since Part D began, Medicare has made additional reinsurance payments to plans after CMS and plan sponsors reconciled claims data. That is, actual spending above Part D’s out-of-pocket threshold was greater, on average, than the amount plan sponsors submitted in their bids. Because enrollee premiums reflect the expected amount of Medicare’s reinsurance rather than the actual amount, enrollee premiums were lower than what they otherwise would have been.

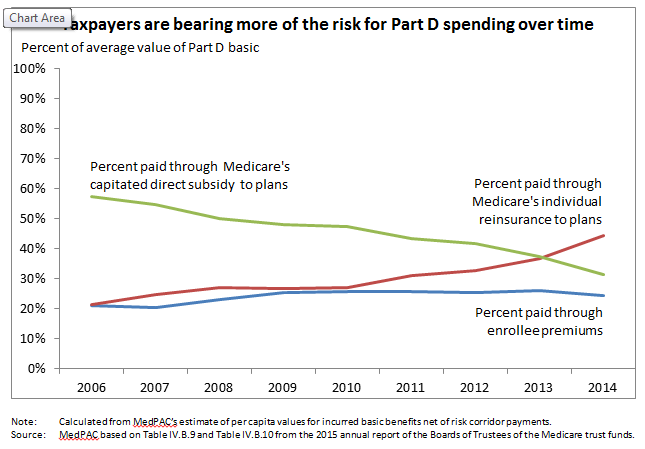

A cornerstone of Part D is that plan sponsors bear insurance risk on drug spending: If a plan’s enrollees spend more on benefits than the combination of Medicare’s fixed-dollar payments and enrollee premiums, the plan will lose money. This insurance risk provides incentives for sponsors to offer attractive benefits yet manage their enrollees’ drug spending through formularies and other tools. However, over time, more and more of Medicare’s Part D subsidies have taken the form of individual reinsurance on which sponsors bear limited risk rather than fixed-dollar direct subsidy payments. Based on data released recently by the Medicare Trustees, the portion of average benefits paid through Medicare’s capitated direct subsidy payments to plans fell from 57 percent in 2007 to 31 percent in 2014. Meanwhile, the portion paid through Medicare’s reinsurance subsidies grew from 21 percent to 46 percent over the same period. If this trend continues, Medicare’s payments for Part D become closer to cost-based reimbursement that relies on open-ended reinsurance payments than one that relies on capitated payments. This is a particular concern going forward because launch prices for new drugs have reached levels that may push more beneficiaries over Part D’s out-of-pocket threshold.

CMS’s latest announcement about bids and data from the latest Trustees’ Report on Part D spending are consistent with trends the Commission has observed over the last several years. (See June 2015 report for the latest data.) While the dollar amounts of average enrollee premiums and Medicare’s direct subsidy payments have remained relatively flat, reinsurance spending has grown rapidly. These patterns may suggest that Part D’s current risk-sharing structure, designed initially to encourage plans to enter the market for providing Medicare’s prescription drug benefit, today may not provide adequate incentives for plan sponsors to manage drug spending of high-cost enrollees.

Now that the market is well established, it may be time to reevaluate policy goals for risk sharing in Part D. Policymakers may want to consider changes in Part D’s risk-sharing mechanisms that encourage plan sponsors to better manage drug benefits for higher cost enrollees. One option would be to require plans to include more of the costs of catastrophic spending in their covered benefits. Under this option, Medicare’s overall subsidy would remain at 74.5 percent, but the makeup of Medicare’s subsidy would change—plan sponsors would receive less individual reinsurance and a larger (capitated) direct subsidy payment. Because a larger share of Medicare’s subsidy would take the form of capitated payments and less in the form of open-ended payments for individual reinsurance, plan sponsors would be at risk for more of covered benefits. While greater risk may provide plan sponsors with stronger incentives to manage benefit spending, such a policy also raises the question of whether plans could or would be more effective at managing their enrollees’ spending than they are today. Several program modifications may be necessary at the same time to achieve the goal of increasing the program’s efficiency. For example, policymakers may consider policy changes that would give sponsors greater flexibility to manage high drug spending. (See the June 2015 report and March 2014 report for additional background information on this topic.)